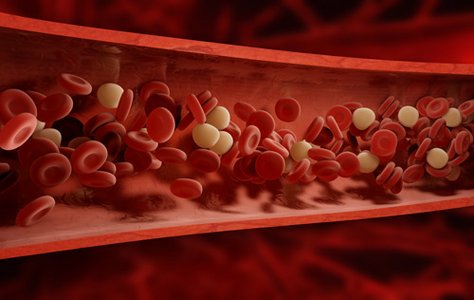

Blood clotting - a blessing and a curse at the same time

Blood clotting is vital: when blood vessels are damaged, the platelets (thrombocytes) clump together and various proteins combine. This quickly creates a clot that closes the defect and prevents further valuable blood from escaping.

Unfortunately, blood clotting also occurs where obstructions cause turbulence in the bloodstream or where the diameter of the vessel is already narrowed, e.g. due to calcification. If a clot (thrombus) has then formed, in the worst case it can block the entire vessel. The result is a thrombosis, e.g. a deep vein thrombosis. The blood can no longer flow through the blocked vessel, damaging the tissue.

In addition to this direct effect, it can also happen that the clot is suddenly washed away (thromboembolism). It is then not uncommon for it to reach the lungs, heart or brain, for example, where it blocks a blood vessel. The associated tissue is then no longer supplied with sufficient blood and is therefore severely damaged.

Who needs anticoagulants?

The main reasons for prescribing anticoagulant medication are atrial fibrillation, deep vein thrombosis and artificial heart valves. However, patients with coronary heart disease, for example, also receive them. Depending on the disease, a different group of active ingredients may be suitable.

Blood thinners - how do they work?

Anticoagulants are also commonly referred to as "blood thinners", but this is not entirely accurate. Anticoagulants do not make the blood more fluid, they reduce the blood's ability to clot. This can happen in different ways:

- Platelet aggregation inhibitors such as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor reduce the clumping of platelets.

- Direct anticoagulants (DOACs such as apixaban, dabigatran and rivaroxaban) intervene in the system of so-called coagulation factors: they inhibit their effect and thus directly inhibit blood clotting.

- Indirect anticoagulants such as vitamin K antagonists (coumarins) or heparin block the production of coagulation factors and thus indirectly inhibit blood clotting because the necessary substances are missing.

Who are platelet aggregation inhibitors suitable for?

Platelet aggregation inhibitors are used to prevent strokes and heart attacks, particularly in cases of coronary heart disease. Those affected then take low doses (e.g. 100 mg ASA daily) on a long-term basis. Platelet aggregation inhibitors can cause stomach problems if the dosage is too high, but overall they are relatively harmless and well tolerated.

When are direct oral anticoagulants used?

DOACs (direct oral anticoagulants, also known as new oral anticoagulants, NOACs) are particularly suitable for patients with atrial fibrillation and symptomatic heart failure. They are also used after surgery, a stroke or a blood vessel occlusion (embolism).

If a patient copes well with DOACs, the blood values need to be checked less frequently than with other anticoagulants. They are a good alternative if regular measurement is not possible. People who do not respond well to vitamin K antagonists also benefit from DOACs.

DOACs are less suitable for people with kidney problems. If they are taken together with antiplatelet agents, this can increase their effect.

The classic among anticoagulants: Vitamin K antagonists

For acute embolisms and thromboses as well as after a heart attack, vitamin K antagonists are the drug of choice for thrombosis prophylaxis. This means that these drugs prevent the formation of new blood clots or at least significantly reduce the risk of them.

It is important to find the right dose for each individual patient, as every body reacts differently to these drugs. Vitamin K antagonists are not suitable for people with treatment-resistant high blood pressure, severe renal insufficiency or a high risk of bleeding (stomach ulcers, aneurysms).

The advantage of vitamin K antagonists is: Their effect can be reversed via the administration of vitamin K. This means that if an operation is imminent or serious injuries occur due to an accident, for example, the effect can be stopped quickly.

Success monitoring using Quick or INR value

In order to monitor the effect of anticoagulant medication, the so-called Quick value used to be determined. It indicates the speed of blood clotting. The normal values for healthy men and women are 70-120, whereas if someone is taking vitamin K antagonists, for example, they are 15-36.

However, as the Quick value can vary somewhat more depending on the measurement method, the INR value (international normalised ratio) is used today. It indicates the factor by which the clotting time of the blood is extended when a blood thinner is taken. The INR value is normally between 0.85 and 1.15, and 2.0-3.5 when treated with blood thinners.

Everyday life with blood thinners

As every patient is different, it is important for the doctor to find the best medication for everyone. As with all medications, it is particularly important to take anticoagulants regularly and exactly as prescribed. Sudden discontinuation without medical supervision can have dangerous consequences.

People who take anticoagulant medication regularly also need to pay attention to a few things in everyday life. Although reduced blood clotting is desirable, it naturally also poses a risk of bleeding during operations or injuries. Anticoagulants can also interact with other medications. You should therefore consult your doctor again if you have any questions about a new prescription.

A medication record card, which lists all medications that are taken regularly, makes it easier for the doctor to keep track in an emergency. An example for patients who take oral anticoagulants can be found here: